The background has already been given in previous posts, but

for convenience will be summarized below. But first I'll present

the suggestions in the hope that readers may remember or guess enough

to follow the discussion.

1) In a previous post I wrote down four hypothetical "marginals"

which are derived from a quantum state (|1>|1> + |-1>|-1>)/\sqrt{2} :

(In case you've forgotten what "hypothetical marginal" means in this context,

I'll summarize later.)

Previous posts have noted that showing that there is a "local realistic"

theory that can reproduce quantum mechanics just for this state is

equivalent to showing that these hypothetical marginals are true marginals

for some probability distribution on the set of 16 outcomes (i,j,k,m)

where the entries i,j,k,m take on the values +1 or -1.

Some people claim to be able to prove that the desired distribution

p(i,j,k,m) does exist. The claimed proof is written in different notation

which makes it difficult for me to extract its claimed p in explicit form.

But for such simple hypothetical marginals, one would expect that if such

a p exists, it ought to be possible to find it explicitly.

An explicit presentation would only require specifying 16 probabilities

from which one could easily check by hand that they do indeed yield the

hypothetical marginals as true marginals. Taking into account the Alice-Bob

symmetry of the underlying quantum state and the fact that all the probabilities

must sum to 1, actually only 7 probabilities need be specified.

Someone who is more familiar with the proof than I (assuming for the sake of

discussion that the proof is correct) may be able to immediately write down p .

Or, if not, then the problem of finding p explicitly

looks like an interesting new line of research. In general, one would hope

for an algorithm for p which would apply to any quantum state, not just

the particular one given above.

If the proponents of the proof could explicitly produce p ,

that would instantly demolish any suspicions that the proof must be wrong

because it contradicts the conclusion of Bell's theorem.

(It would not prove that the proof is correct for general states,

but then at least people would take it seriously.)

That p reproduces the hypothetical marginals as true marginals

would be indisputable because it could be checked by simple arithmetic

which could be done by hand in a few minutes. Few will argue with

arithmetic!

Production of p would also show beyond any doubt that traditional

proofs of Bell's theorems are wrong. This would be huge news that

would rock the scientific world, given that many consider Bell's Theorem,

simple as it is, one of the major scientific advances in centuries.

In short, my first suggestion is that those who believe that local realistic

theories can reproduce quantum mechanics should demonstrate the truth of

a small part of their belief by explicitly exhibiting p for the above

simple marginals. Those marginals do not satisfy the hypotheses of

several forms of Bell's theorem, so that p would be an indisputable

counterexample to Bell's theorem.

2) This suggestion will describe a simple experiment that anyone with

a computer algebra system (such as Mathematica, Maple, or one of the free

systems like MacSyma) can do to try to find a p which reproduces the

hypothetical marginals.

As noted above, to find p it is enough to find seven probabilities

which satisfy some inhomogeneous linear equations. There are four

marginals, each with four entries, so there are 4x4=16 equations in all

for the 7 unknowns. Generically, we wouldn't expect a solution to 16 linear

equations in only 7 unknowns, but the way the equations were obtained

and the symmetries of the hypothetical marginals gives hope

that a solution might be possible.

Looking at it another way, we could go back to our original 16 probabilities

as unknowns, adjoin one equation specifying that the probabilities

sum to 1, and obtain 16+1=17 equations in 16 unknowns, which looks not

so overdetermined.

It would probably take less than an hour to type the linear system into

a computer algebra system. Because the entries of the hypothetical

marginals are rational numbers, an exact solution will be obtained if

the system is consistent.

If the system of equations is inconsistent (i.e., has no solution),

the computer algebra program will report that. That will show that

there is no local realistic theory (according to all definitions

that I have seen) which can reproduce the predictions of quantum mechanics

for the above state. This is the conclusion of Bell's theorems whose

usual proofs I believe to be correct, so this is what I think will happen.

(I have not invested the time to actually do the experiment because

I am so sure of the outcome!)

If the system proves consistent, the algebra program will give it explicitly,

but there will be more to be done because we need a solution for which

all probabilities are non-negative. This converts the problem into one

of so-called "linear programming", about which I know little, but I wouldn't

be surprised if computer algebra programs could do that, too. (The manual

for mine just says that it will "try" to find a solution!)

Even if not, the problem is so small that given the explicit solution,

one might be able to find a non-negative solution by hand.

If so, that would settle by explicit arithmetic that Bell's theorem is incorrect.

It would suggest, but not prove, that perhaps local realistic theories might reproduce

the predictions of quantum mechanics, thus shattering a belief almost universally

held among professional physicists. The effort involved seems small enough that it seems

worth a try by the "anti-Bellians" given that debate within this forum seems to have reached an impasse.

I chose the above marginals because of their numerical simplicity,

to produce a concrete context within which the Bell's theorem debate

in this forum might be settled without controversy.

Of course, explicitly exhibiting p for those particular marginals

would not prove that one could find p for all marginals

predicted by quantum mechanics for all quantum states.

But it would suggest hope for that possibility.

______________________________________________________________________

The rest of this post summarizes previus posts.

Consider a probability distribution p = p(i,j,k,m) defined on the

set of all 4-tuples (i,j,k,m) with each entry

i,j,k,m equal to either +1 or -1.

For example, a typical outcome is (+1, -1, -1, +1).

Its first entry +1 may be regarded as the result of measuring a quantity

which we denote A, the second as the result of measuring a quantity A',

the third of measuring B, and the fourth of measuring B'.

From p we can derive various "marginal" probability distributions,

"marginals" for short, an example of which is

where the sum ranges over all possible j and m (each being +1 or -1).

Marginals pAB', pA'B , and PA'B' are defined similarly. (There

are other marginals as well, but we will not be concerned with them.)

Consider the following purely mathematical question:

Given four probability distributions pAB , pAB' , pA'B , and pA'B'

on the probability space consisting of all ordered pairs (u,v) with

entries +1 or -1,

does there exist a p = p(i,j,k,m) for which these are the corresponding

marginals?

Of course, the answer will depend on the given (hypothetical) marginals;

for some marginals it might be possible and for others impossible.

There is a mathematical theorem giving necessary and sufficient conditions

for the existence of p , but to make my question as concrete

as possible, consider a numerical special case.

Consider the following "hypothetical marginals" pAB and pA'B,

presented as 2x2 matrices:

'

This presentation is to be interpreted according to the usual matrix

convention that pAB(1,1) = 3/8 = pAB(-1,-1) , pAB(1,-1) = 1/8 = pAB(-1,1) ,

etc. I call them "hypothetical marginals" because we cannot assume,

a priori, that they can be derived from some p = p(i,j,k,m) .

They are just four 2x2 matrices that we can write down.

Continuing, define

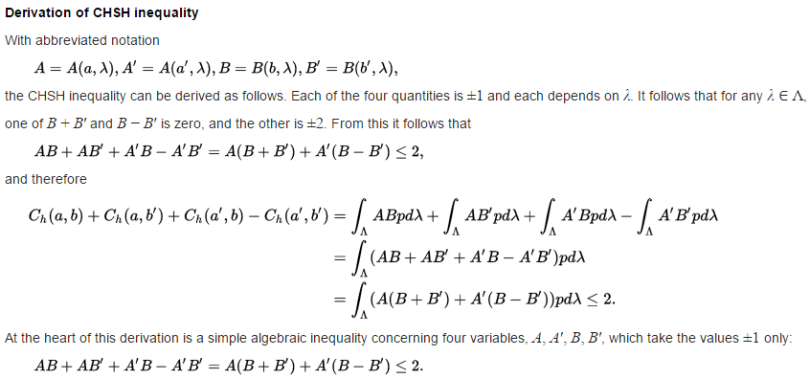

The following is a purely mathematical theorem with a simple proof

which has surely been checked by thousands of mathematicians.

I, myself, have checked it and consider the possibility of an error

in its proof as similar to the probability of an error in the Binomial

Theorem. It has nothing to do with physical measurements, though

it can be interpreted in that context.

Theorem: There is no probability distribution p(i,j,k,m) which

yields the above hypothetical marginals pAB , pA'B , pAB' , pA'B'

as true marginals.

The theorem is a special case of Bell's theorem.

Despite the simplicity of its statement and proof,

it is considered one of the most important scientific

advances of the past centuries. If it is false or even if there is

any mistake in any of its accepted proofs, that will be huge news,

shaking the scientific establishment to its roots.

Some theorems have proofs so complicated that their status

(true or unproved or false) remains in doubt for years.

To show that a theorem is false, it is sufficient to produce a counterexample.

This is often easier than arguing about a complicated proof which few

understand.

Some members of this forum believe that accepted proofs

of the above theorem are false,

and others vigorously dispute that claim.

Somebody who wants the fame of rocking the scientific establishment

would probably be well-advised to look for a counterexample when arguments

about established proofs have proved inconclusive.